March 2022, 62 murders in a single day are registered in El Salvador. This marks the deadliest day in the country since the end of the Salvadoran Civil War in 1992 – an anti-celebration of sorts for a country that used to hold the title of the homicide capital of the world just a few years back.

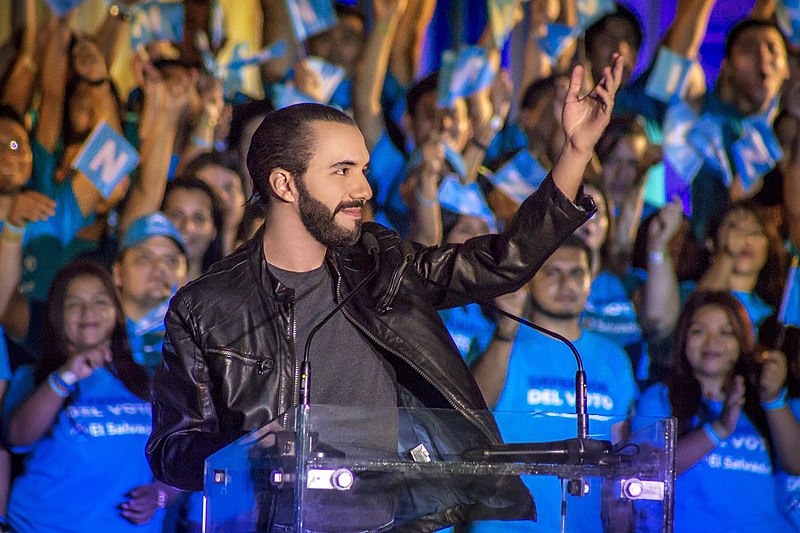

In the following days, following President Nayib Bukele’s request, the Salvadoran government announced a 30-day state of emergency, during which, certain civil liberties would be abolished. Following this, in September of this year, the President announced that he would be running again in the upcoming presidential election after the end of his term, despite the ban on consecutive re-election in the country’s constitution.

With government reforms primarily focusing on containing gang violence in the country and the introduction of new constitutional reforms that are in violation of the rule of law, including prematurely replacing incumbent Supreme Court judges with Bukele’s loyalists earlier this year and overriding the ban on presidential re-election, the already fragile democracy of El Salvador is being challenged, perhaps irreversibly.

The modern history of El Salvador has been marked by civil unrest. Since the early 1930s until 1979, the country had been ruled by a military dictatorship. Paradoxically, the end of military rule in El Salvador was marked by the start of a bloody civil war that lead to the deaths of tens of thousands. After the Peace Accords were signed in 1992 ending the civil war, the country was able to establish basic democratic norms through reforms made in the judicial and electoral systems. Yet, democratisation did not end the track record of organized violence in El Salvador.

By the end of the civil war, at least a quarter of the Salvadoran population had fled to the US, predominantly to Los Angeles. In the US, the Salvadoran immigrant community grew marginalised and was frequently exposed to racial hierarchies imposed by other gangs that had been operating in the country. As such, out of fear, and as a way to protect their community, Salvadoran immigrants started setting up gangs of their own, later transforming into a hands-on criminal network within the US. By the time Salvadoran gangs became infamous to the US public, the Clinton administration took on the task of deporting Salvadorans who engaged in criminal activities back to El Salvador.

Fresh out of the civil war, El Salvador was still relatively ill-equipped to deal with the influx of Salvadoran deportees. The country lacked the basic infrastructure that would allow it to re-integrate the thousands of Salvadoran “newcomers” previously trained in gangs. Neglected and left with no governmental support, Salvadorans who had already mastered how to organize criminal gang activities back in the US found themselves looking for opportunities to survive. Extortion through torture and killings became the only foreseeable solution to the everyday problems of living in El Salvador for many of these gangs and their members.

Gang members practised extortion by building up local power positions in (mainly) poor neighbourhoods of Salvadoran towns and cities where residents would have to pay ‘rent’ to gang members in order to be spared their lives. Without much government control, such violent networks increased their size and wealth ultimately transforming themselves into the prime national security threat.

Organised crime in El Salvador is implicitly challenging state power through de-facto territorial control of the country’s marginalised areas. Unsurprisingly, the Salvadoran gang “issue” was declared a full-scale national security threat and automatically reached top-priority level on the political agendas of the country’s leaders. As such, the incumbent President Nayib Bukele and his predecessors made numerous attempts to fight gang violence by introducing strict anti-gang policy measures which thus far have only proven to be short-term solutions, never really helping to eliminate or even weaken gang organisations in the country.

During the state of emergency period announced earlier this year, Bukele celebrated drops in murder rates, ensuring that Salvadoran citizens, exhausted from years of grief afflicted upon them by the country’s gangs, see that the government’s policies are working. But despite this, human rights activists and journalists in and outside the country are claiming that President Bukele’s ‘war on gangs’ came at the cost of Salvadoran citizens’ human rights.

While the emergency measures were in place, thousands of Salvadorans were arrested of which the President admitted a number could potentially be arrested arbitrarily. In some cases, arrests were based on the grounds of having physical attributes associated with being a gang member – such as tattoos – or on an arrest quota scheme imposed on the police by their superiors, as some investigators have claimed.

All this whilst Salvadoran and global media investigations suggest that drops in murder rates were achieved through negotiations between gang leaders and the government, where in exchange for financial favours from the public officials, gangs would stop their usual violent activities to help the President and his party continue enjoying high approval ratings.

As such, it seems as though President Bukele’s “war on gang” policies are costing the country its democratic quality. At most, anti-gang policies are a one-time solution and a potential distraction from systematic problems that are facing the country and enabling the functioning of gangs. These include poorly functioning security policies, a lack of social and economic opportunities as well as general neglect of the country’s youth, whose vulnerabilities can be easily exploited by gang members in recruitment. As such, this tunnel vision on the issue of gang violence employed by El Salvador’s government, be it for gaining political capital or lower homicide rates, is keeping the country from reaching its fullest potential to achieve a functioning democracy.

Leave a comment